|

I just got a tour of Switch Communications Group’s (Las Vegas) newest colocation facility, which is due to open in one month. Known as SuperNAP (NAP stands for Network Access Point), it is being billed as the densest, safest and most interconnected data center in the world.

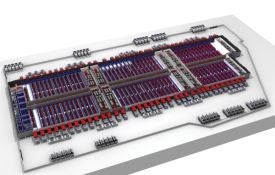

Switch Communications Group’s SuperNAP Colocation Facility in Las Vegas aims to match blade density with affordable power and cooling. Will it be a lucky bet for power-starved enterprises?

It’s a monster: 407,000 square feet with 250 Megavolt Amperes (MVA) of substation and 146 MVA of diesel generator capacity. That’s enough room for more than 7,000 racks, each capable of in-excess of 17 kW. In other words, you can pack each rack to capacity with blades — four chassis worth of blade servers and it can take the load.

As most IT managers know, the majority of data centers can host only a certain number of blades due to their massive power and cooling demands. So you typically see the odd rack of blades surrounded by less-demanding gear — or even blades at the bottom part of the cabinet with plenty of empty space above them. And, of course, there are those operations with boxes of blades sitting in a storeroom while they figure out where on earth they are going to get the power and cooling to feed them.

|

Recent Hard-Core Hardware

» Green Is the New Black » Dell Acquisition May Shake Up Server Marketplace » Hard Drive, RIP More Hardware |

Some vendors, of course, boast of the potential to jam 30 kW or more into one rack. But the infrastructural realities are such that this almost never occurs. In fact, the Uptime Institute recommends 1.9 kW per rack as a best practice for dense data centers.

Why can SuperNAP do better? Gone are raised floors and the traditional pattern of cold aisles and hot aisles. Switch reverses the typical arrangement by having the cold air come from above to be channeled down onto the servers.

“A raised floor goes against the laws of physics, as cold air falls and hot air rises,” said Missy Young, executive vice president of sales engineering at Switch.

|

| The SuperNAP Colocation Facility |

Once the air runs through the servers, it doesn’t just vent back into the room. The hot aisles are completely contained within what is known as a Thermal Separate Compartment in Facility (T-scif). The hot air is then fed above the ceiling and sucked back into the building’s cooling system. Thus, the hot air is completely contained and not allowed to mix with the cold at any time.

The cooling budget is kept lower courtesy of Switch’s own cooling system design. 70 percent of the time, outside air is used. This reduces the need to rely on massive cooling towers and the requirement for Niagara-like water consumption. Different types of cooling systems are used to maximize efficiency, depending on ambient conditions.

|

Unsure About an Acronym or Term? |

As SuperNAP is situated in Nevada several miles from the Vegas strip, it is in the fortunate position of having high quantities of power available that can be fed directly into the facility. Hence, the company’s plans to triple the size of SuperNAP from its initial 407,000 square feet in the next couple of years. Power availability won’t be the constraint it is in metro areas, such as Los Angeles, New York and Chicago.

The electrical side could compose an entire article, but there is no room in this piece. Suffice to say, it contains 84 MVA of UPS supplied by APC, countless APC PDUs, and switching gear and breakers from SquareD (all Schneider Electric companies).

|

| Inside the SuperNAP Colocation Facility |

The Vegas location also helps sweeten the deal for potential customers on two fronts — disaster recovery and network connectivity. Nevada is outside of all major disaster zones — earthquake, flood, tornado, ice storm, and hurricane — and thus, it does not suffer from power cuts associated with natural disasters.

Further, the Switch site provides high redundant bandwidth on the cheap — something good that came out of the collapse of Enron. One of Enron’s last grand schemes was to become a bandwidth-trading powerhouse. As its star was so high with all the major telecom carriers frantically building out their fiber optic networks at the end of the last millennium, Enron convinced 17 of them to bring their networks directly into the Enron facility. Switch bought the whole set up for pennies on the dollar and can now offer clients wholesale prices on high bandwidth.

Result: 500 racks of space in the new building have already been sold — before a single server was brought in. Sales of another 1,500 racks are pending or in negotiation. Young expects to sell out within a year or so.

Next week, I’ll cover the repercussions of such mega-colo plants and what this means for the data center industry as a whole — and how it may well exert a huge impact on server OEMs, too.